Heidegeris

Ieškoti atitikmenų

- Concern

- Temporality

- Being-toward-Death (Sein-zum-Tode)

Atitikmenys mano filosofijos

- Kodėl: Being and Thinking - Thinking (Kodėl) išplečia Being - bet Being siejama su tiesa

- Kaip: Being and Becoming

- Koks: Being and Seeming

- Ar: Being and the Ought - Being išplečia Ought (Ar) - bet Being siejama su

Šešerybė: rūpesčio būsenos, išorinės ir vidinės

- Thrownness - Disposedness (nuotaika) nuoširdumas-artimumas teisingumas-susivaldymas

- Fallenness - Understanding (pasirinkimas tolimo vietoj artimo laiko) viltis-meilė pareiga-rūpestis

- Projecting - Fascination drąsa-žavesys ištikimybė-tikėjimas

- Take-other-beings-as = įžvelgti, pripažinti besąlygiškumą

- Dasein=having-to-be-open = privalantis pripažinti besąlygiškumą

- Taking-as = dėl to, kad esame baigtiniai

- present-as .... present-at-hand?

Būtis apimtyse

- Būtis kaip Ar: Being towards death (Sein-zum-Tode) - turime savo vaidmenį - liudyti, tad mirti, tad amžinai gyventi

- Būtis kaip Koks: fenomenologinis, those things are which show themselves to be - Being in general

- Būtis kaip Kaip: In-sein

- Būtis kaip Kodėl: Aš (niekas): kalbinis "Aš" Being already in - mano laisvės pagrindas, galiu nuo visko atsiplėšti, atsiriboti savimi - Being already in ... Being one's self?

Būtis sąryšyje: being thrown

- Concern - Sein zu (didėjantis laisvumas - ateitis - projection)

- Mood - In-der-Welt-sein (mažėjantis laisvumas - praeitis - thrownness)

7-tas Being together with (Sein bei), Being with = They (Mitsein)... Kitus esančiuosius, visuomenę, suvokiame, kaip mūsų pasaulį, sutapatiname su pasauliu. Kitais suvokiame save taip, kad tapatinamės su pasauliu, su visuomene.

8-tas - amžinas gyvenimas? rūpesčių išsirišimas, tai, kad esame palaikomi (Selbstein?) atsiplėšimas nuo visuomenės - yra kažkas daugiau

- Being with others = su mumis kiekvienu - su bendru žmogumi, kuriam prieinami įrankiai

- Mood - nuotaika=nusiteikimas (praeitis)

- Concern (besorgen) - rūpintis=rūpinimasis (dabartis)

- Care (Sorge) - rūpestis=rūpėjimas (ateitis)

Kodėl mes esame? Esame susieti su visakuo. Vadinas, būtent Dievas (Nežinojimas) mus žino (žinodamas viską). Tad mes esame žinomi, o tas žinojimas yra už mūsų pasaulio. Ogi jis tatai (Dievą) išbraukė užtat ir nuvertino. Tad jame nėra to supratimo, kaip būtent Nežinojime slypi ir atsiskleidžia visas žinojimas.

Žinojimas: Tūlas. Nežinojimas: Esantysis.

Visko savybės - ką mums gali reikšti "pasaulis" - koks gali būti jo santykis su mumis:

- neturi aplinkos: 3. "World" can be understood in another ontical sense—not, however, as those entities which Dasein essentially is not and which can be encountered within-the-world, but rather as the wherein a factical Dasein as such can be said to 'live'. "World" has here a pre-ontological existentiell signification. Here again there are different possibilities: "world" may stand for the 'public' we-world, or one's 'own' closest (domestic) environment.

- viską priima: 1. "World" is used as an ontical concept, and signifies the totality of things which can be present-at-hand within the world.

- neturi sandaros: 2. "World" functions as an ontological term, and signifies the Being of those things we have just mentioned. And indeed 'world' can become a term for any realm which encompasses a multiplicity of entities: for instance, when one talks of the 'world' of a mathematician, 'world' signifies the realm of possible objects of mathematics.

- būtina sąvoka: 4. Finally, "world" designates the ontologico-existential concept of worldhood (Weltheit). Worldhood itself may have as its modes whatever structural wholes any special 'worlds' may have at the time; but it embraces in itself the a priori character of worldhood in general.

Šaltiniai

- palyginti su Being and Becoming, su Introduction to Metaphysics:

Užrašai

Interpretation - ratas - trejybė.

ieškoti ketverybės: what, how

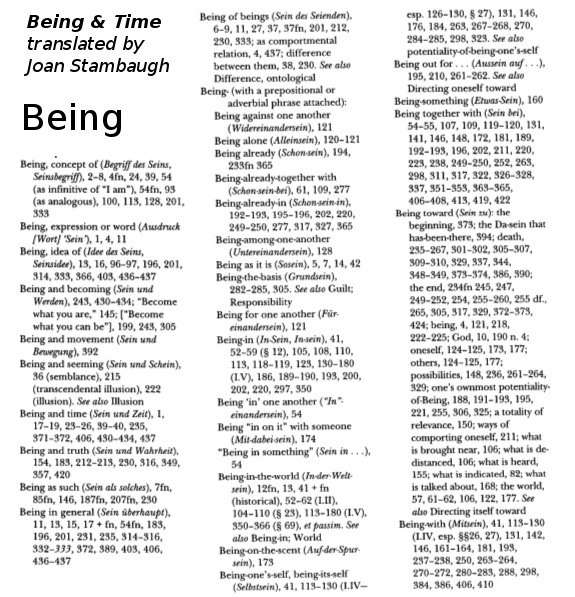

Being

- Dasein. Dasein has various modes of being-in-the-world. A being that is there, in a familiar world, and in a mood; whose being is an issue for itself; participates in discourse; with a sense of "mineness," or being one's self; always thrown into the world, meaning it finds itself within a world, meaning no Dasein has ever been decontextualized; engaged with our surroundings through care, concern, and moods. An understanding of being as What things are and That they are.

Dasein yra susijęs su savo sąlygomis.

Modes of Dasein

- Being one's self (Selbstein) ideal mode of existence of Dasein

- Being with (Mitsein) We are with others and necessarily influenced by them.

- Being together with (Sein bei) Discourse with others because of our shared thrownness and projection.

Additionally

- Being toward (Sein zu) Concern (towards the world we find ourselves in)

- Being in the world (In-der-Welt-sein) Mood. We are inseparable from the world, always under some mood. However, we can take responsibility for that mood.

- Being in (In-Sein, In-sein) Being in (In-Sein, In-sein)"Being in something or other" like water in a glass, "the-Being-present-at-hand-as-things-within-the-world", "Being-present-at-hand-along-with", a characteristic in our way of looking at things categorically.

- Being already in (Schon-sein-in) Being-already-at-hand is a notion of the subject as "an essence," as happens linguistically, where every Being becomes a "thing", every thing becomes a name, Dasein becomes "I" and the world becomes a collection of predicates which lie always outside of the "I".

- Being in general (Sein ueberhaupt) Being in general is always the Being of some entity or another, which shows itself as it is.

- Being thrown (Geworfen) into the world, non-mastery of its own origin and referential dependence on other beings.

- Being towards death (Sein-zum-Tode) Death is Dasein's ownmost (it is what makes Dasein individual), it is non-relational (nobody can take one's death away from one, or die in one's place, and we can not understand our own death through the death of other Dasein), and it is not to be outstripped.

- Being-taken-as Aristotle holds that since every meaningful appearance of beings involves an event in which a human being takes a being as—as, say, a ship in which one can sail or as a god that one should respect—what unites all the different modes of Being is that they realize some form of presence (present-ness) to human beings. This presence-to is expressed in the ‘as’ of ‘taking-as’. Thus the unity of the different modes of Being is grounded in a capacity for taking-as (making-present-to) that Aristotle argues is the essence of human existence. Heidegger's response, in effect, is to suggest that although Aristotle is on the right track, he has misconceived the deep structure of taking-as. For Heidegger, taking-as is grounded not in multiple modes of presence, but rather in a more fundamental temporal unity (remember, it's Being and time, more on this later) that characterizes Being-in-the-world (care).

- Being toward (Sein zu) - Because Being-in-the-world belongs essentially to Dasein, its Being towards the world is essentially concern.

- Being together with (Sein bei) The ontological-existential structure of Dasein consists of "thrownness" (Geworfenheit), "projection" (Entwurf), and "being-along-with"/"engagement" (Sein-bei). These three basic features of existence are inseparably bound to "discourse" (Rede), understood as the deepest unfolding of language.

- Being with (Mitsein) An ontological characteristic of the human being, that it is always already with others of its kind. We are inauthentic when we fail to recognize how much and in what ways how we think of ourselves and how we habitually behave is influenced by our social surroundings. We are authentic when we pay attention to that influence and decide for ourselves whether to go along with it or not. Living entirely without such influence, however, is not an option.

- Being in the world (In-der-Welt-sein) His replacement for the subject/object, consciousness/world distinctions. All consciousness is consciousness of something. (Ryšys tarp Dievo ir Manęs-Gerumo). There is always a mood assailing us, and it comes from being-in-the-world. (Tai mūsų riba su pasauliu - tai apimties nusakyta riba.) Our facticity is that we can only go from mood to mood. Only by moods we can encounter things in the world. Dasein takes responsibility for its mood, understands its possibilities as possiblities, rather than just follow along, as in the case of the They. Dasein projects itself upon its possibilities and interprets and understands the world in terms of them. The structure of Being-in-the-world consists of items which actually may be looked at in three distinct ways:

- 1/ in terms of the world or Worldhood.

- 2/ In terms of Who - the entity which in every case has Being-in-the-world as the way in which it exists is a "who."

- 3/ In terms of Being-in = This conception looks at the ontological constitution of the "Inhood" of Being-in. [ref. ¶ 12, page 78 - 79]

The ways in which Dasein's Being takes on a definite character, and they must be seen and understood a priori as grounded upon that state of Being which we have called "Being-in-the-world'. The compound expression 'Being-in-the-world' stands for a unitary phenomenon.

- Being in (In-Sein, In-sein) "Being-in" is a term we usually associate with our involvement in a situation or a context. Thus, "Being in" is not thought about solely in isolation, but in terms of "Being in something or other". For example we can say that: the water is in the glass, However, in terms of inness the description cannot be terminated with that proposition for is not the glass also in the kitchen, which is in the house, which is in the village, which is in the county and so on until we realise that, in terms of inness, the glass (and everything else described) are actually located in worldspace. Thus, the inness of "Being-in-the-world" or to put it more precisely, this inness can be defined as, "the-Being-present-at-hand-as-things-within-the-world". This present-at-hand type of 'Being-in' can be further isolated into "Being-present-at-hand-along-with". This sense here is that the Being-present-at-hand describes a definite relationship of location, where something exists with something else; both having the same kind of Being. This sense of 'Being-in' thus can be used as a way to describe patterns of existence and is therefore an example of a characteristic in our way of looking at things categorically [ref. ¶ 12, page 79] Being-in does not suggest a spatial relationship of the "in-one-anotherness" of things present at hand, anymore than Heidegger's use of the word primordially signifies a spatial relationship. [ref.¶ 12, page 80]. As Heidegger later points out the spatial quality of an entity can only be clarified in terms of it Being part of the structure of worldhood, not as its apriori spatial condition. This conception is contrary to Kant's famous transcendental phenomenology which regards space and time as the a priori conditions that make the perception of reality possible. Heidegger contends that we will not be able to discover the world if we take spatiality as its grounding apriori condition [ref. ¶ 14, page 93].

- Being already in (Schon-sein-in) Ontologically every idea of a 'subject'--unless refined by a previous logical determination of its basic character--still posits what maybe called in Scholastic language the subjectum (which Heidegger translates as "Being-already-at-hand"). This notion of the subject possesses an what might be called "an essence," no matter how many vigorous ontical protestations the advocates of this doctrine care to make against the "soul substance" or the "reification of consciousness" etc. Heidegger argues that such reification always going to happen in the arena of language - where every Being becomes a "thing" and every thing becomes a name. In this paradigm, Dasein becomes "I" and the world becomes a collection of predicates which lie always outside of the "I". Only by using the phenomenological method can the ontological origin of these terms be demonstrated and can this dogma be contested. However such knowledge is certainly not available to any logical proof (since logic itself is predicated on grammar and on language and these ways of understanding the world and ourselves have already cut Being out of the equation!) So if we are to manoeuvre ourselves into a position from where we can ask the question, "What do we understand positively when with think of this unreified Being that we have hitherto considered to be the subject, soul, consciousness, spirit, person, etc?" we must do two things:

- 1/ Appreciate how all these "subjectum" terms in fact refer to definite phenomenological domains which can be 'given form', using the phenomenological method.

- 2/ Be aware that this method cannot be employed unless we first take on board the idea that the Being of these entities is what is being designated and not the 'thingness' of them.

- Being one's self (Selbstein) ideal mode of existence of Dasein

- Being out for (Aussein auf)

- Being the basis (Grundsein)

- Being of beings (Sein des Seiende)

- Being in general (Sein ueberhaupt) The ancient Greek expression phenomenon is derived from the verb "to show itself". To show itself, in ancient Greek, also connoted "bringing something to the light". In this sense, phenomenon signifies, "that which shows itself in itself." This signification of phenomenon alludes to the fact that an entity can show itself for itself in many ways, depending on the kind of access we have to it. Indeed it is even possible for an entity to show itself as something it is not. The use of the term "phenomena" is restricted in Heidegger's usage to designate only those things that show themselves for themselves. Other forms of showing are given the terms seeming and appearing . [ref. ¶ 7, Page 51] Phenomena when understood phenomenologically are nothing but the fragments, so to speak, that go to make up the whole phenomenon of Being in general. I choose the word fragment here to liken the concept of a particular Being to the fragment of a broken mirror. A fragment of a broken mirror is, in terms of its substance, merely part of a greater whole (the whole mirror). Yet in terms of what it reflects, the fragment can not be differentiated, since the part can potentially reflects the same scene as the whole. The variable in this case if what way you view the fragment. We can push this analogy to its limit and say that an appreciating Being in general is dependent on how you view the individual Being. As Heidegger says, Being in general is always the Being of some entity or another. In other words, if we find a way to view the reflection in the mirror that 'belongs' to it and all its fragments, then we are able to see the nature of Being in general. Therefore, in our investigation of the meaning of Being, we should first bring forward entities in themselves and discover their Being. For the two reasons:

- 1/ there is nothing behind phenomena and

- 2/ phenomena cannot lie.

- Therefore all entities must show themselves phenomenologically in themselves and for themselves with the kind of access that genuinely belongs to them. [ref. ¶ 7, Page 61]

- Being thrown (Geworfen) Geworfenheit describes our individual existences as "being thrown" (geworfen) into the world. This single term, "thrown-ness," "describes [the] two elements of the original situation, There-being's non-mastery of its own origin and its referential dependence on other beings".

- Being towards death (Sein-zum-Tode) For Heidegger, death is Dasein's ownmost (it is what makes Dasein individual), it is non-relational (nobody can take one's death away from one, or die in one's place, and we can not understand our own death through the death of other Dasein), and it is not to be outstripped.

- Dasein. A being that is there, in a familiar world, and in a mood. Dasein also has unique capacities for language, intersubjective communication, and detached reasoning. Dasein is a being whose being is an issue for itself; every Dasein has an a priori sense of "mineness," or being one's self; Dasein is always thrown into the world, meaning it finds itself within a world, meaning no Dasein has ever been decontextualized. We are all world-bound, submerged, entangled, and engaged with our ontico-ontological surroundings through care, concern, and moods. Dasein has various modes of being-in-the-world. Humans have a pre-ontological (general intuitive sense of being) understanding of being insofar as they understand What things are and That they are. This pre-reflective understanding of being, that which determines entities as entities, helps constitute our unique existence as human beings.

Yeremias Jena The modes of existence of Dasein in the world are Being-with-the-other (Mitsein), Being-alongside-things (Sein-bei), and Being-one’s-self (Selbstein). [su Tavimi, su Kitu, su Savimi] For Heidegger, the ideal mode of existence of Dasein is Being-one’s-self (Selbstein). Only through this mode of being that Dasein forms its distinctiveness from other entities which are just being-within-the-world. As to the convenience of enjoying the objects of the world, idle talk or gossipping can cause Dasein to forget its authentic being. After describing the thoughts of Heidegger on the fall of Dasein into being unauthentic, this paper highlights the ontological awareness of the existence of Dasein towards death as an authentic mode of existence. At the end of this writing, I propose narration as a ‘tool’ to be used by health care providers in assisting the patient to affirm and accept illness experience as their modes of being.

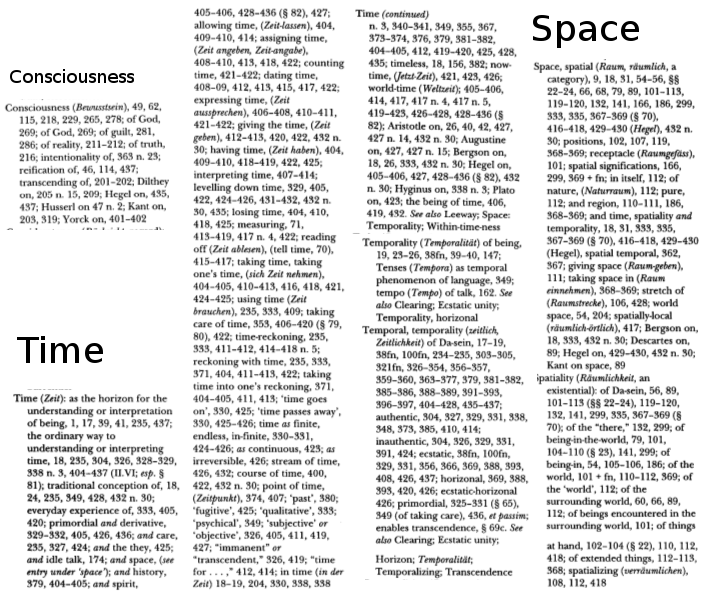

Laikas ir erdvė

- Heidegger's Being and Time, part 8: Temporality Simon Critchley

- Stanford Internet Encyclopedia: Temporality and Temporalizing

Laikas

- Esantysis save suvokia savo galimybėmis. O galimybės išsipildo laike.

- Kasdienis gyvenimas: eiliškumas. Pakylame iš eiliškumo klausimu, kuo Esantysis skiriasi nuo visų kitų esančių? (Nes jisai yra nuoroda sau

Laikiškumas

- temporality is the a priori transcendental condition for there to be care (sense-making, intelligibility, taking-as, Dasein's own distinctive mode of Being).

- Moreover, it is Dasein's openness to time that ultimately allows Dasein's potential authenticity to be actualized: in authenticity, the constraints and possibilities determined by Dasein's cultural-historical past are grasped by Dasein in the present so that it may project itself into the future in a fully authentic manner, i.e., in a manner which is truest to the mine-self.

- Kant's claim that embeddedness in time is a precondition for things to appear to us the way they do. (According to Kant, embeddedness in time is co-determinative of our experience, along with embeddedness in space.)

- Time thought of in either of the ways below is a present-at-hand phenomenon, and that means that it cannot characterize the temporality that is an internal feature of Dasein's existential constitution, the existential temporality that structures intelligibility (taking-as).

- absolute clock-time (an infinite series of self-contained nows laid out in an ordering of past, present and future)

- relatively measured - some sort of relativistic phenomenon that would satisfy the physicist

- To make sense of this temporalizing, Heidegger introduces the technical term ecstases. Ecstases are phenomena that stand out from an underlying unity. (He later reinterprets ecstases as horizons, in the sense of what limits, surrounds or encloses, and in so doing discloses or makes available.)

- temporality is a unity against which past, present and future stand out as ecstases while remaining essentially interlocked.

- the easiest way to grasp Heidegger's insight here is to follow him in explicitly reinterpreting the different elements of the structure of care in terms of the three phenomenologically intertwined dimensions of temporality.

- Dasein's existence is characterized phenomenologically by thrown projection plus fallenness/discourse.

- Heidegger argues that for each of these phenomena, one particular dimension of temporality is primary.

Thrownness=Praeitis

- thrownness is identified predominantly, although not exclusively, as the manner in which Dasein collects up its past (finding itself in relation to the pre-structured field of intelligibility into which it has been enculturated),

- fallen-ness and discourse are identified predominantly, although not exclusively, as present-oriented (e.g., in the case of fallen-ness, through curiosity as a search for novelty in which Dasein is locked into the distractions of the present and devalues the past and the projective future).

Projection=Praeitis

- projection is disclosed principally as the manner in which Dasein orients itself towards its future. Anticipation, as authentic projection, therefore becomes the predominantly futural aspect of (what we can now call) authentic temporalizing, whereas expectation, as inauthentic projection, occupies the same role for inauthentic temporalizing.

- The discussion of being-towards-death in blog six led to the idea of anticipation, namely that the human being is always running ahead towards its end. For Heidegger, the primary phenomenon of time is the future that is revealed to me in my being-towards-death. Heidegger makes play of the link between the future (Zukunft) and to come towards (zukommen). Insofar as Dasein anticipates, it comes towards itself. The human is not confined in the present, but always projects towards the future.

- But what Dasein takes over in the future is its basic ontological indebtedness, its guilt, as discussed in the previous blog. There is a tricky but compelling thought at work here: in anticipation, I project towards the future, but what comes out of the future is my past, my personal and cultural baggage, what Heidegger calls my "having-been-ness" (Gewesenheit). But this does not mean that I am somehow condemned to my past. On the contrary, I can make a decision to take over the fact of who I am in a free action. This is what Heidegger calls "resoluteness".

Dabartis

- This brings us to the present. For Heidegger, the present is not some endless series of now points that I watch flowing by. Rather, the present is something that I can seize hold of and resolutely make my own. What is opened in the anticipation of the future is the fact of our having-been which releases itself into the present moment of action.

- This is what Heidegger calls "the moment of vision" (Augenblick, literally "glance of the eye"). This term, borrowed from Kierkegaard and Luther, can be approached as a translation of the Greek kairos, the right or opportune moment.

- Heidegger argues that because future-directed anticipation is intertwined with projection onto death as a possibility (thereby enabling the disclosure of Dasein's all-important finitude), the “primary phenomenon of primordial and authentic temporality is the future” (Being and Time 65: 378), whereas inauthentic temporalizing (through structures such as ‘they’-determined curiosity) prioritizes the present.

- However, since temporality is at root a unitary structure, thrownness, projection, falling and discourse must each have a multi-faceted temporality. Anticipation, for example, requires that Dasein acknowledge the unavoidable way in which its past is constitutive of who it is, precisely because anticipation demands of Dasein that it project itself resolutely onto (i.e., come to make its own) one of the various options established by its cultural-historical embeddedness. And anticipation has a present-related aspect too: in a process that Heidegger calls a moment of vision, Dasein, in anticipating its own death, pulls away from they-self-dominated distractions of the present.

Svarbiausia:

- since futurality, historicality and presence, understood in terms of projection, thrownness and fallenness/discourse, form the structural dimensions of each event of intelligibility, it is Dasein's essential temporality (or temporalizing) that provides the a priori transcendental condition for there to be care (the sense-making that constitutes Dasein's own distinctive mode of Being).

Tolima praeitis, dabartis, ateitis - autentiška. Artima praeitis, ateitis - neautentiška.

Kaip nusprendžiau visom progom mąstyti lietuvių kalba

- This sets the stage for Heidegger's own final elucidation of human freedom. According to Heidegger, I am genuinely free precisely when I recognize that I am a finite being with a heritage and when I achieve an authentic relationship with that heritage through the creative appropriation of it.

Mirtis

Buvimas myriop (Sein zum Tode) yra trilypis Būties sąlyga. Laikas, dabartis ir amžinybė yra trys laikiškumai. (Zeitlichkeit) Ekstazės (Ekstase) - (išėjimas?) už savęs, ateities projekcijos, buvimas praeityje kaip dalis savo kartos, tautos. Mirtis yra ta galimybė kuri yra Esančiojo negalimybė. (Tai (neigiamai) atitinka Dievo išėjimui už savęs, iškritimas iš jo žaidimo.) Mirtis yra savita-nesusijusi, užtikrinta (neapeinama), neapibrėžta (nenumatyta), ir nepralenkiama savo svarba (unüberholbar).

Palyginti "savo Mirties" ir Dievo savybes:

- mano Mirtis yra savarankiška (su kitais nesusijusi)

- užtikrinta (neapeinama)

- rami (neapibrėžta, nenumatyta)

visgi Dievas yra mylintis (trokšta visko, pripažįsta kažką daugiau), tuo tarpu Mirtis yra nemylinti (ji nepralenkiama savo svarba).

- Mirtis priverčia susirūpinti gyvenimu - betgi galima susirūpinti gyvenimu ir nepaisant Mirties.

- Mirtis leidžia suvokti jog nesame šiaip žmonės, jog esame kažkas daugiau, šio pasaulio neaprėpiamo. Jog galim gyventi širdies tiesa, ne pasaulio tiesa.

- Heidegeris teigia, kad mirtis mus "suneramina" ir tad ištraukia iš pasaulio tiesos į širdies tiesą. Bet iš tikrųjų yra atvirkščiai. Mums labai įvairiai kyla nerimas, ir būtent kada gyvename pasaulio tiesa vietoj kad širdies tiesa. Ir būtent nerimas kyla kada paskęstame pasaulyje.

Telling someone to "remain in the present" could then be self-contradictory, if the present only emerged as the "outside itself" of future possibilities (our projection; Entwurf) and past facts (our thrownness; Geworfenheit).

Spatiality, Temporality, and the Problem of Foundation in Being and Time. Yoko Arisaka.

- Heidegger distinguishes three different types of space: 1. world-space, 2. regions (Gegend), and 3. Dasein's spatiality.

- Heidegger makes the following five distinctions between types of time and temporality: 1. the ordinary or "vulgar" conception of time; this is time conceived as Vorhandenheit. 2. world-time; this is time as Zuhandenheit. Dasein's temporality is divided into three types: 3. Dasein's inauthentic (uneigentlich) temporality, 4. Dasein's authentic (eigentlich) temporality, and 5. originary temporality or “temporality as such.”

- In addition to its spatial Being-in-the-world, Dasein also exists essentially as "projection." Projection is oriented toward the future, and this futural orientation regulates our concern by constantly realizing various possibilities. Temporality is characterized formally as this dynamic structure of "a future which makes present in the process of having been" (BT 374, 326). Heidegger calls the three moments of temporality--the future, the present, and the past--the three ecstases of temporality (BT 377, 329). This mode of time is not normative but rather formal or neutral; as Blattner argues, the temporal features which constitute Dasein's temporality describe both inauthentic and authentic temporality.

- The second alternative is to treat temporality as having some content above and beyond care: "the three-fold constitution of care stems from the three-fold constitution of temporality"

- In this reading, "temporality temporalizing itself," "Dasein's projection," and "the temporal projection of the world" are three different ways of describing the same "happening" of Being-in-the-world, which Heidegger calls "self-directive" (BT 420, 368).

- This equiprimordial unity is more explicitly stated in HCT; remotion [de-severance], region, and orientation [directionality] are the "three interconnected phenomena" which define the structure of the aroundness of the world as well as the spatiality of Dasein. These spatial phenomena are the three aspects of Being-in-the-world (cf. Section 25).

Erdvė

- ‘De-severing’ amounts to making the farness vanish—that is, making the remoteness of something disappear, bringing it close”

- Heidegger argues that existential space is derived from temporality. This makes sense within Heidegger's overall project, because, as we shall see, the deep structure of totalities of involvements (and thus of equipmental space) is finally understood in terms of temporality. Nevertheless, and although the distinctive character of Heidegger's concept of temporality needs to be recognized, there is reason to think that the dependency here may well travel in the opposite direction. The worry, as Malpas (forthcoming, 26) again points out, has a Kantian origin. Kant (1781/1999) argued that the temporal character of inner sense is possible only because it is mediated by outer intuition whose form is space. If this is right, and if we can generalize appropriately, then the temporality that matters to Heidegger will be dependent on existential spatiality, and not the other way round.

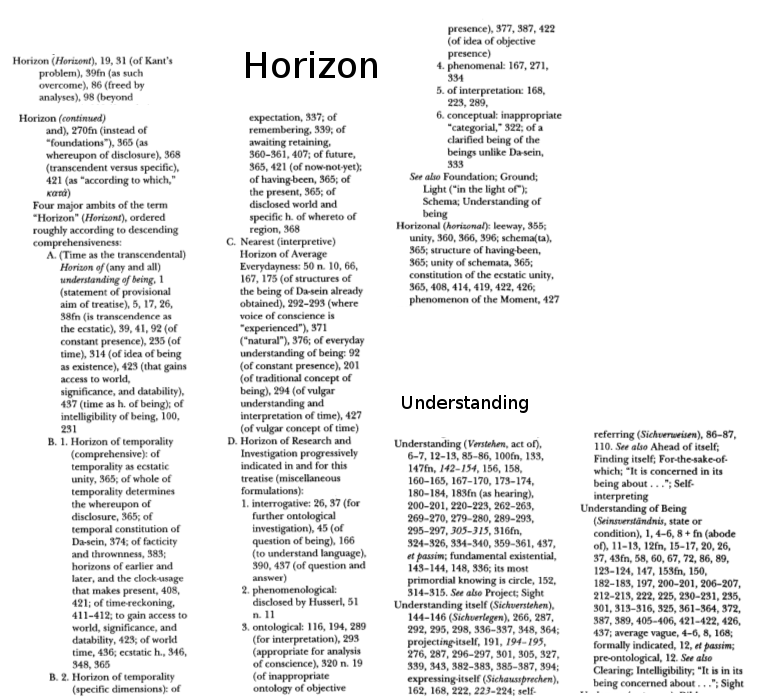

Horizon

- A. (Time as the transcendental) Horizon (of any and all) understanding of being

- B. Horizon of temporality

- Comprehensive

- Specific dimensions: expectation, remembering, awaiting retaining, future, now-not-yet, present, disclosed world

- C. Nearest (interpretive) Horizon of Average Everydayness

- D. Horizon of Research and Investigation progressively indicated in and for this treatise

- 1. interrogative

- 2. phenomenological

- 3. ontological

- 4. phenomenal

- 5. interpretation

- 6. conceptual

Understanding

- Understanding (Verstehen)

- Understanding itself (Sichverstehen, Sichverlegen)

- Understanding of Being (Seinsverstaendnis)

- grasp = pagriebti, nusitverti = "laikyti" = suvokti

- grasp = Griff (rankena) = begreifen = suvokti

Existential

Topologies

- Two related words, existenziell and Existential, are used as descriptive characteristics of Being. To be existenziell is a categorical or ontic characteristic: an understanding of all this which relates to one's existence, while an Existenzial is an ontological characteristic: the structure of existence.

- Categorial: Of or pertaining to the being of entities unlike Dasein. Contrasts with "existential."

- Category: An essential feature of the being of non-Dasein entities. Contasts with "existentiale."

- Existential: Of or pertaining to the being of Dasein. Contrasts with "categorial."

- Existentiale: An essential feature of Dasein, i.e., an element of the being of Dasein. (Contrasts with "category.")

- Existentialia: The plural form of "existentiale."

- Existentiell: Of or pertaining to Dasein as an entity, in contrast with the being of Dasein. (It is an existential feature of Dasein that it understands, but an existentiell feature of Jones that she understands herself as a baseketball player, say.)

Entities present-at-hand within the world are understood ontically and their characteristics can be arranged into categories. Dasein on the other hand is understood ontologically and its characteristics are arranged into existentiale. The difference between existentiale and category is both in the way they are used (existentiale applies only to Dasein, category applies to entities within the world) but in the different paradigmatic assumptions (the differences between an ontical and ontological understanding) that underpin them.

In traditional philosophy, categories are defined as tools for analysis. For example, in Aristotle's Organon, categories enumerated all the possible kinds of thing which can be the subject or the predicate of a proposition. The classical Aristotelian view that claims that categories are discrete entities characterized by a set of properties which are shared by their members. These are assumed to establish the conditions which are both necessary and sufficient to capture meaning. Therefore the tradition of categorisation instigated by Aristotle, ideally illuminates a relationship between the subjects and objects of knowledge (source - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Categorization).

The use of categories is predicated on the assumption that reality can be studied by slicing it into parts and grouping those parts into sets, based on some perceived similarity between the parts. In the traditional philosophical paradigm, this slicing is not seem in terms of doing violence to the 'wholeness of reality', for the wholeness of reality is considered to be a mystery that needs to be taken apart and analysed in order to be understood. In addition, one also has to bear in mind that the violence of cutting up objects for study in this way in no way effects the person who is studying them. Since this person, as a subject, is detached from the objects of study and emotionally indifferent to them. However in Heidegger's ontological paradigm, such distinctions collapse and therefore the assumptions upon which are based also collapse.

Heidegger argues, when we encounter entities in the world, we already address ourselves to the question of their Being. This is meant in the sense of when a child points at something and asking "what's that?" the gesture and the question already implies that she is aware that there is a 'Being' there in need of a name. Moreover, the "what's that" question also points to the fact that there is 'something' which is already distinguishable from the manifold of the world, in other words which stands out from the rest in terms of its Being. According to Heidegger, the action of addressing oneself to an entity's Being is what the ancients understood by the term 'category'. Their use of category signifies making a public accusation, in the sense of asking someone to account for their actions in front of witnesses. When used ontologically, the term category has a similar meaning - a kind of putting things on trial, but in this case what is made to account for itself is the Being of entity itself. In other words, the particular kind of language we use to determine a category lets everyone else see the object in terms of its Being. When we use Language in this way it allows us to uncover the "what's that?" of an object's Being that exists before it is named. The Categories are therefore what are 'sighted' in words (the logos), which implies the articulation of an explicit description of the Being of a given entity, rather than the covering over of that Being of that entity with a name. [ref. ¶ 9, page 70]

Būtis

Palyginti būtį ir aplinkybes.

- 1/ "Being is not a genus". It has been maintained that Being is the most universal of concepts, thus an understanding of Being is presupposed in our conceiving of anything as an entity. Being transcends any categorical distinction we care to make in our apprehension of the world. It does this by existing above and beyond any notion of a category that we can form in our understanding.

- 2/ Being is indefinable. The term entity cannot be applied to Being because it cannot be defined using traditional logic, (i.e. a technique for understanding which derives its terms either from higher general concepts, or by recourse to ones of lower generality). In other words, because Being is neither a thing nor a genus it follows that it cannot be defined according to logic, whose job is to set out the rules that govern the categorisation of phenomena and concepts.

- 3/ Being is self-evident. Whenever one thinks about anything, or makes an assertion, or even asks a question; some use is made of Being. But the intelligibility of Being, in this sense, is only an average sort of intelligibility (common sense understanding). This average intelligibility is also indicative of its scholarly unintelligibility, i.e., the way that the question: "what is Being?", is often ignored in philosophical investigations.

- 1/ Dasein is a Being who understands that it exists, and what is more the Being of Dasein is, in part, shaped by that understanding.

- 2/ The above statement can be seen to serves as a working definition of the formal conception of existence,

- 3/ Dasein exists and moreover Dasein and existence are one. For example if Dasein is 'the human Being' and existence is 'the world,' then Dasein and the world are one. The consequence of this is that Dasein and existence cannot be separated - even analytically separated.

- 4/ Dasein is also an entity which I myself am. In other words each one of us (as human Beings) defines existence in terms of our own existence, a concept that Heidegger terms Mineness. Therefore the only way that Being can be understood is as My Being.' This applies even when Being and Dasein are considered in general.

- 5/ Mineness belongs to any existent Dasein, in the sense that how I regard 'my Being', creates the conditions that make authenticity and inauthenticity possible. [ref. ¶ 12, page 78]

Ketverybė

- For-the-sake-of-which: That as which Dasein understands itself, that is, the self-understanding or existential possibility for the sake of which Dasein acts. A for-the-sake-of-which is not a goal, some definite project that Dasein can complete, but rather something deeper and less well-defined, such as being a student, being a mother, being the black sheep in the family. The distinction becomes really important in Division Two.

- Significance: The relational whole of "signifying" relations. Signifying relations are the relations that bind together the many different sorts of entity that show up or make sense in terms of the world. Paraphernalia makes sense in terms of its role in Dasein's practices; those roles make sense in terms of further roles; and all these items ultimately make sense in terms of the human possibilities for the sake of which Dasein acts. Thus, paraphernalia, cultural roles, and for-the-sakes-of-which are all bound together by a set of relations that makes up the structure of the world. That relational system is significance. Significance is the "worldhood of the world," thus the being of the world: the world is a set of entities (paraphernalia, tasks, roles, for-the-sakes-of-which) bound together by a set of relations. The relations (abstracted from the entities) make up significance. Thus, significance is the "webbing" that holds the web of the world together. It is the internal structure of the world.

Not feeling at home in the world...

Rūpestis

- Dasein's facticity is such that its Being-in-the-world has always dispersed itself or even split itself up into definite ways of Being-in. The multiplicity of these is indicated by the following examples: having to do with something, producing something, attending to something and looking after it, making use of something, giving something up and letting it go, undertaking, accomplishing, evincing, interrogating, considering, discussing, determining. . . .[12]

- All these ways of Being-in have concern (Sorge, care) as their kind of Being. Just as the scientist might investigate or search, and presume neutrality, we see that beneath this there is the mood, the concern of the scientist to discover, to reveal new ideas or theories and to attempt to level off temporal aspects.

- Care is synonymous with Dasein because Being-in-the-world belongs essentially to Dasein. In actual fact, this is what is meant by the meaning of Being conceived of as "I reside alongside"--see Being (the formal understanding of). Dasein's Being is always looking out towards the world is therefore is essentially manifested in care and concern. And also the ontological conception of Being-in as the "alongsidedness of things," suggests both their close proximity to Dasein, and also their intimate intertwining with Dasein.

- In making the Being of Dasein visible as care, care itself must be taken as an ontological structural concept. In this sense, care has nothing to do with its everyday significations of "trials and tribulations", or "being bound up in the 'cares of life'." Although, it is true that ontically we can come across these aspects of care in every Dasein. And, like the opposite state of 'gaiety'-- which in its true signification means 'a freedom from care'--they are only possible because Dasein is synonymous with care when understood ontologically. [ref. ¶ 12, page 84]

- The ontical meaning of concern comes in three colloquial significations:

- 1/ 'to carry something out,' or 'to get it done.'

- 2/ 'to provide oneself with something' and

- 3/ 'to be concerned about the success of the undertaking'.

- In contrast to these ontical significations, the ontological expression 'concern' designates - the Being of a possible way of Being-in-the-world. Thus concern is an existentiale and the term has been chosen because it allows us to make visible the Being of Dasein as care. Dasein's facticity is such that its Being-in-the-world has always dispersed itself into definite ways. A primary characteristic of Dasein is that it is a Being concerned with its own existence. [ref. ¶ 12, page 84]

- We are all world-bound, submerged, entangled, and engaged with our ontico-ontological surroundings through care, concern, and moods.

- the ready-to-hand only emerges from the prior attitude in which we care about what is going on and we see the hammer in a context or world of equipment that is handy or remote, and that is there "in order to" do something. In this sense the ready-to-hand is primordial compared to that of the present-at-hand.

Heidegerio rūpesčiai

- "Aš" kaip asmuo grindžiasi medžiaga, substancija.

- The introduction of the ‘they’ is followed by a further layer of interpretation in which Heidegger understands Being-in-the-world in terms of (what he calls) thrownness, projection and fallen-ness, and (interrelatedly) in terms of Dasein as a dynamic combination of disposedness, understanding and fascination with the world. In effect, this is a reformulation of the point that Dasein is the having-to-be-open, i.e., that it is an a priori structure of our existential constitution that we operate with the capacity to take-other-beings-as.

- the dimensionality of care will ultimately be interpreted in terms of the three temporal dimensions: ** past (thrownness/disposedness),

- future (projection/understanding), and

- present (fallen-ness/fascination).

Past

- I ineluctably find myself in a world that matters to me in some way or another. This is what Heidegger calls thrownness (Geworfenheit), a having-been-thrown into the world. ‘Disposedness’ is Kisiel's (2002) translation of Befindlichkeit, a term rendered somewhat infelicitously by Macquarrie and Robinson as ‘state-of-mind’. Disposedness is the receptiveness (the just finding things mattering to one) of Dasein, which explains why Richardson (1963) renders Befindlichkeit as ‘already-having-found-oneself-there-ness’. To make things less abstract, we can note that disposedness is the a priori transcendental condition for, and thus shows up pre-ontologically in, the everyday phenomenon of mood (Stimmung). According to Heidegger's analysis, I am always in some mood or other. Thus say I'm depressed, such that the world opens up (is disclosed) to me as a sombre and gloomy place.

- As one might expect, Heidegger argues that moods are not inner subjective colourings laid over an objectively given world (which at root is why ‘state-of-mind’ is a potentially misleading translation of Befindlichkeit, given that this term names the underlying a priori condition for moods). For Heidegger, moods (and disposedness) are aspects of what it means to be in a world at all, not subjective additions to that in-ness. Here it is worth noting that some aspects of our ordinary linguistic usage reflect this anti-subjectivist reading. Thus we talk of being in a mood rather than a mood being in us, and we have no problem making sense of the idea of public moods (e.g., the mood of a crowd).

- As one might expect, Heidegger argues that moods are not inner subjective colourings laid over an objectively given world (which at root is why ‘state-of-mind’ is a potentially misleading translation of Befindlichkeit, given that this term names the underlying a priori condition for moods). For Heidegger, moods (and disposedness) are aspects of what it means to be in a world at all, not subjective additions to that in-ness. Here it is worth noting that some aspects of our ordinary linguistic usage reflect this anti-subjectivist reading. Thus we talk of being in a mood rather than a mood being in us, and we have no problem making sense of the idea of public moods (e.g., the mood of a crowd).

Sąvokų suvokimas "kaip" tinkle

- Dasein confronts every concrete situation in which it finds itself (into which it has been thrown) as a range of possibilities for acting (onto which it may project itself). Insofar as some of these possibilities are actualized, others will not be, meaning that there is a sense in which not-Being (a set of unactualized possibilities of Being) is a structural component of Dasein's Being. Out of this dynamic interplay, Dasein emerges as a delicate balance of determination (thrownness) and freedom (projection). The projective possibilities available to Dasein are delineated by totalities of involvements, structures that, as we have seen, embody the culturally conditioned ways in which Dasein may inhabit the world. Understanding is the process by which Dasein projects itself onto such possibilities. Crucially, understanding as projection is not conceived, by Heidegger, as involving, in any fundamental way, conscious or deliberate forward-planning. Projection “has nothing to do with comporting oneself towards a plan that has been thought out” (Being and Time 31: 185). The primary realization of understanding is as skilled activity in the domain of the ready-to-hand, but it can be manifested as interpretation, when Dasein explicitly takes something as something (e.g., in cases of disturbance), and also as linguistic assertion, when Dasein uses language to attribute a definite character to an entity as a mere present-at-hand object. (NB: assertion of the sort indicated here is of course just one linguistic practice among many; it does not in any way exhaust the phenomenon of language or its ontological contribution.) Another way of putting the point that culturally conditioned totalities of involvements define the space of Dasein's projection onto possibilities is to say that such totalities constitute the fore-structures of Dasein's practices of understanding and interpretation, practices that, as we have just seen, are projectively oriented manifestations of the taking-as activity that forms the existential core of Dasein's Being. What this tells us is that the hermeneutic circle is the “essential fore-structure of Dasein itself” (Being and Time 32: 195).

Dabartis

- Thrownness and projection provide two of the three dimensions of care. The third is fallen-ness. “Dasein has, in the first instance, fallen away from itself as an authentic potentiality for Being its Self, and has fallen into the world” (Being and Time 38: 220). Such fallen-ness into the world is manifested in idle talk (roughly, conversing in a critically unexamined and unexamining way about facts and information while failing to use language to reveal their relevance), curiosity (a search for novelty and endless stimulation rather than belonging or dwelling), and ambiguity (a loss of any sensitivity to the distinction between genuine understanding and superficial chatter). Each of these aspects of fallen-ness involves a closing off or covering up of the world (more precisely, of any real understanding of the world) through a fascination with it. What is crucial here is that this world-obscuring process of fallen-ness/fascination, as manifested in idle talk, curiosity and ambiguity, is to be understood as Dasein's everyday mode of Being-with. In its everyday form, Being-with exhibits what Heidegger calls levelling or averageness—a “Being-lost in the publicness of the ‘they’ ” (Being and Time 38: 220).

- In utilizing public means of transport and in making use of information services such as the newspaper, every Other is like the next. This Being-with-one-another dissolves one's own Dasein completely into a kind of Being of ‘the Others’, in such a way, indeed, that the Others, as distinguishable and explicit, vanish more and more. In this inconspicuousness and unascertainability, the real dictatorship of the ‘they’ is unfolded. We take pleasure and enjoy ourselves as they take pleasure; we read, see, and judge about literature and art as they see and judge; likewise we shrink back from the ‘great mass’ as they shrink back; we find ‘shocking’ what they find shocking. The ‘they’, which is nothing definite, and which all are, though not as the sum, prescribes the kind of Being of everydayness. (Being and Time 27: 164)

- This analysis opens up a path to Heidegger's distinction between the authentic self and its inauthentic counterpart. At root, ‘authentic’ means ‘my own’. So the authentic self is the self that is mine (leading a life that, in a sense to be explained, is owned by me), whereas the inauthentic self is the fallen self, the self lost to the ‘they’. Hence we might call the authentic self the ‘mine-self’, and the inauthentic self the ‘they-self’, the latter term also serving to emphasize the point that fallen-ness is a mode of the self, not of others. Moreover, as a mode of the self, fallen-ness is not an accidental feature of Dasein, but rather part of Dasein's existential constitution. It is a dimension of care, which is the Being of Dasein. So, in the specific sense that fallen-ness (the they-self) is an essential part of our Being, we are ultimately each to blame for our own inauthenticity

Autentiškumas

- savitumas

- kyla iš Esančiojo savybės "Aš"

- Autentiškumas - širdies tiesa (pirminė), neautentiškumas - pasaulio tiesa (antrinė).

- Autentiškumą grindžia savivoka (o tai dvigubas požiūris į save: tai savęs suvokimas, atskyrimas, vertinančiojo ir vertinamojo: koks esu ir koks turėčiau būti: taigi, jų atskyrimas yra autentiškas, o jų sutapimas yra pasekmė, bet jau neautentiška, nepirminė, tik išraiška).

- Andrius: autentiškumas yra nuolatinis savęs tikrinimas. Iš šalies atrodo visai klaidingai.

- nesavitumas rūpinasi tikrumu (actuality), o savitumas - galimybe

Esančiojo aplinkybės:

- Nuotaika

- Suvokimas

- Kalba

Būties raiškos

- Esantys (daiktai) ir Esantysis (asmuo).

- Išmonės: daiktų mokslai ir asmenų pasaulėžiūros.

- Klaidų pagrindai: tarnavimas sau (daiktams) ar Dievui (asmenims)

- Kategorijos esantiems ir egzistencialai Esančiajam.

Heidegerio klaidos

- Jis nepagalvojo: "Esu, vadinas veikiu."

- Disclosure: suvokimas tikslo.

Wikipedia

Heidegeris nesutinka Platonu ir Aristoteliu, kad išstūmė laiką iš mąstymo akiračio. Akį iškėlė prieš kitas jusles. Iškėlė amžinųjų esačių virš šios laikinos esybės. Reikia išmokti mąstyti esmingai šiapusybę.

Being-in-the-world [Įveltumas. Neatplėšiamumas. Nuojautos buvimas.] Heidegerio klaida - nesuvokimas, jog galime būti ramūs, galime to siekti.

Dvejybės atvaizdas:

- Present-at-hand [teorija]. Apophantic [teiginys]. Ontic [aprašymas].

- Ready-to-hand [praktika]. Equipment. Ontological [išgyvenimas].

Manau, kad Heidegeris klydo pirmenybę teigdamas "ready-to-hand". Turėtų būti atvirkščiai, širdies tiesa yra mūsų išskirtinumas nuo mūsų aplinkybių.

- Dasein savita, autentiška [Širdis]. Existence. World [Aplinkybės]. Geworfenheit [Įmestinumas]. Disclosure, or "world disclosure" [Liudijimas].

- The One (Tūlas) nesavita, neautentiška [Pasaulis].

Pirmiausiai pristatysiu savo pratimus, kuriais atskiriu autentišką, savitą, "širdies" tiesą (vidinę tikrovę) ir neautentišką, nesavitą, "pasaulio" tiesą (išorinę tikrovę). Toliau tvirtinsiu, jog Heidegeris klydo manydamas, kad parankiškumas ir buvimas-pasaulyje yra autentiški.

Heidegeris norėjo kovoti su sustaburėjusia mąstysena ir paprieštarauti subjekto ir objekto, asmens ir daikto atskirčiai. Užtat jisai iškėlė Esančiojo (Dasein) ir jo aplinkybių vientisumą sąvoka "buvimu-pasaulyje". Visgi, jisai paskui prieštaravo sau pripažindamas, jog esantysis pasaulyje ištisai jaučiasi nesavitas.

Panašu, kad Heidegeris negalvojo, kad žmogus gali jaustis ramus. O aš savo pratimais parodau, kad žmogus iš tiesų ramus kada jisai mąsto teisingai, kada nesupainioja širdies ir pasaulio tiesų. Heidegeris galvojo, kad žmogus visada bandomas ūpų ir nuotaikų. Sutinku, kad dažnai taip būna, bet ne ištisai. Tiktai vėliau Heidegeris iškėlė sąvoką Gelassenheit, lūkesčio nebuvimą, sąlygojantį ramybę.

Drįstu manyti, jog Heidegeris klydo teigdamas pirmenybę "parankiškumui" (praktikai) ir ne "daiktiškumui" (teorijai). Iš tiesų, aiškinsiu, jog mūsų prote teorinis požiūris veda į praktinį požiūrį bet ne atvirkščiai. Visos širdies tiesos jau glūdi mumyse, o pasaulio tiesas turime išmokti. Širdies tiesos yra dviprasmiškos, užtat atitrūkusios nuo pasaulio, tuo tarpu pasaulio tiesos yra vienareikšmiškos, mus įtvirtinančios pasaulyje. Kūdikėlis įsčiose sėkmingai plėtoja teorijas ir teorinis mąstymas vyrauja naujagimyje. Užtat labai imliai išmokstame kalbas. Tiktai su laiku pasiduodame pasauliui ir visuomenei. Panašiai, Esantysis atsiranda pasaulyje, kaip iš medžio iškritęs. Jo savitumas priklauso nuo jo vidinės nepriklausomybės, jo laisvės spręsti ar jisai pasaulyje pritampa ar nepritampa. Tuo tarpu "tūlas" yra tos laisvės išsižadėjęs. Taigi, širdies tiesos mus moko plėtoti sąvokų ir vertybių kalbą, kuri yra "daiktiška" ir ne "parankiška". Heidegeris teisingai pastebėjo, kad ši kalba per amžius dėsningai išsikvėpė. Bet tai yra kaip tik dėl to, kad kalba virto žodžiais, parankiškomis priemonėmis, ir neliko sąvokomis, savarankiškomis vertybėmis, mus atstovaujančiomis būtybėmis, kurios turėtų amžinai ryškėti, vis naujai atsiskleisti, ir mes jomis.

Heidegeris vėliau tvirtino, jog Esantysis pasaulyje išsikovoja lauką, kuriame Būtis gali pasireikšti tiesa. O tai juk parodo, kad vidinė tikrovė kovoja su išorine tikrove ir gali jai nepaisiduoti. Gera valia atveria laukymę gerai širdžiai reikštis. Panašiai, Heidegeris tvirtino, jog tiesa (akivaizdumas) gali pasireikšti ten kur Esantysis išsaugoja, išsikovoja lauką.

Žodžiu, Heidegeris rašydamas "Būtį ir laiką" rėmėsi klaidomis, kurių nebegalėjo ištaisyti. Užtat manau jis ir negalėjo išbaigti savo veikalo. Įvyko jo posūkis nuo buvimo į glūdimą/gyvenimą. Tai sutampa su mano pastabom.

Apskritai, manau, kad jisai Dievą pakeitė Būtimi. Tai jam suteikė laisvę mąstyti, bet taip pat nutolino jį nuo esmės, nuo Nesančiojo, (nuo Dievo pirm buvimo), ir nuo tiesų, kurių dar niekas nedrįso pasakyti, būtent kad "Dievas nebūtinai geras".

- Dasein is not a thing or substance and is capable of standing outside of the world characterized through its activities of generalization, universalization, abstraction, inference, and so on. This “standing outside”—ec-stasis—is the key to Heidegger’s concept of Understanding in Division I Chapter 6. This sense of transcendence applies fundamentally to Dasein as an activity.

- Būtis yra "vietovardis" kuriuo vadiname klausimą, kurį protas svarsto dvejybe.

- Esančiojo klausimas yra nagrinėjimas savęs: Koks jisai yra? Ar dalyvavimas Dievo klausime: Ar Dievas būtinas?

- Esantysis yra buvimo-pasaulyje veikla.

- Dasein differs from everything else in the universe because it interprets not only what it encounters but itself as well. (So why can't there be that which interprets itself and is prior to everything else in the universe?)

- Being is “made visible in its ‘temporal’ character” in the sense that time is part of the identity and character of things. Dasein is not “in” time like a log floating down a river, it changes through its existence. This will become part of Heidegger’s reversal of Aristotle’s metaphysical principle that essence preceeds existence. For Heidegger, existence is a temporal phenomenon affecting the characterization of something’s essence.

- Even the “supra-temporal” is in time. What philosophy had thought of as timeless entities—Plato’s universals, mathematical truths, the laws of logic and thought—are also temporal. Instead of universals, Heidegger discusses the activity of universalizing first made famous by Plato. Socrates, for example, in the early books of the Republic, wonders how all the various conceptions of justice are related. This leads him to talk about the form of Justice. How did that appeal to universality come to involve the ontology of permanence and timelessness? This is in part a question about how Plato and Aristotle established the traditional activity of philosophy as the search for timeless truths

Branda. Being-toward-death. A process of growing through the world where a certain foresight guides the Dasein towards gaining an authentic perspective. It is provided by dread or death. In the analysis of time, it is revealed as a threefold condition of Being. Death is that possibility which is the absolute impossibility of Dasein.

- death is Dasein's ownmost (it is what makes Dasein individual),

- it is non-relational (nobody can take one's death away from one, or die in one's place,

- and we can not understand our own death through the death of other Dasein), and it is not to be outstripped.

Disclosure: Išmonė, atsivėręs pasaulis, kur gali reikštis reiškiniai. (Dievo Dvasios).

Klaidos

- When tradition thus becomes master, it does so in such a way that what it 'transmits' is made so inaccessible, proximally and for the most part, that it rather becomes concealed. Tradition takes what has come down to us and delivers it over to self-evidence; it blocks our access to those primordial 'sources' from which the categories and concepts handed down to us have been in part quite genuinely drawn. Indeed it makes us forget that they have had such an origin, and makes us suppose that the necessity of going back to these sources is something which we need not even understand. (Being and Time, p. 43)

- With average, everyday (normal) discussion of death, all this is concealed. The "they-self" talks about it in a fugitive manner, passes it off as something that occurs at some time but is not yet "present-at-hand" as an actuality, and hides its character as one's ownmost possibility, presenting it as belonging to no one in particular. It becomes devalued — redefined as a neutral and mundane aspect of existence that merits no authentic consideration. "One dies" is interpreted as a fact, and comes to mean "nobody dies".

- We are inauthentic when we fail to recognize how much and in what ways how we think of ourselves and how we habitually behave is influenced by our social surroundings.

Atitaisymas

- Destruktion. Susprogimas sąvokų, kurias tradicija yra iš ontologinių pavertusi ontikinėmis.

- If the question of Being is to have its own history made transparent, then this hardened tradition must be loosened up, and the concealments which it has brought about dissolved. We understand this task as one in which by taking the question of Being as our clue we are to destroy the traditional content of ancient ontology until we arrive at those primordial experiences in which we achieved our first ways of determining the nature of Being—the ways which have guided us ever since. (Being and Time, p. 44)

- it has nothing to do with a vicious relativizing of ontological standpoints. But this destruction is just as far from having the negative sense of shaking off the ontological tradition. We must, on the contrary, stake out the positive possibilities of that tradition, and this means keeping it within its limits; and these in turn are given factically in the way the question is formulated at the time, and in the way the possible field for investigation is thus bounded off. On its negative side, this destruction does not relate itself toward the past; its criticism is aimed at 'today' and at the prevalent way of treating the history of ontology. .. But to bury the past in nullity (Nichtigkeit) is not the purpose of this destruction; its aim is positive; its negative function remains unexpressed and indirect. (Being and Time, p. 44)

- On the other hand, authenticity takes Dasein out of the "They," in part by revealing its place as a part of the They. Heidegger states that Authentic being-toward-death calls Dasein's individual self out of its "they-self", and frees it to re-evaluate life from the standpoint of finitude. In so doing, Dasein opens itself up for "angst," translated alternately as "dread" or as "anxiety." Angst, as opposed to fear, does not have any distinct object for its dread; it is rather anxious in the face of Being-in-the-world in general — that is, it is anxious in the face of Dasein's own self. Angst is a shocking individuation of Dasein, when it realizes that it is not at home in the world, or when it comes face to face with its own "uncanny" (German Unheimlich "not at home"). In Dasein's individuation, it is open to hearing the "call of conscience" (German Gewissensruf), which comes from Dasein's own Self when it wants to be its Self. This Self is then open to truth, understood as unconcealment (Greek aletheia). In this moment of vision, Dasein understands what is hidden as well as hiddenness itself, indicating Heidegger's regular uniting of opposites; in this case, truth and untruth.

- Being-with [gyvenimas tarp kitų] We are authentic when we pay attention to that influence and decide for ourselves whether to go along with it or not.

- Resoluteness [Atsakomybė sau]

- Ereignis [Įsisavinimas]

Autentiškumas

- Dasein’s existence indicates Dasein’s potentiality for being. We have seen that, with care, Dasein exists “ahead of itself.” Care is related to the unity of Dasein. Over time, Dasein is characterized through its involvements and this is related to the distinction between authenticity and inauthenticity. Authenticity is determined by the stand Dasein takes towards death. If inauthentic being is Dasein’s lack of totality, it is because Dasein is not unified, does not have freedom. Dasein’s “ahead of itself” is indeterminate and inauthentically determined by the one. The encounter with death and with Dasein’s ultimate nothingness outside of its activities constitutes Dasein’s transformation towards authenticity (this is what Heidegger means when he says in #49 that “death is a part of

life”). Death is the limit of Dasein’s being-in the world and the value of this encounter is determined by “conscience” and “guilt”: will Dasein accept responsibility for itself, will it ‘get a life’ or not? Guilt is an aspect of dread, through the characterization of life as thrown (as having no transcendent justification or foundation), so guilt determines the question of responsibility and “conscience”: will Dasein accept a unifying role or not? Finally, the point of the entire book is that all of this takes place in time, which characterizes Dasein’s existence. Death thus forms the transcendental limit (horizon) for the temporality of life (“the end”).

Užrašai

- Atsiriboti nuo žinojimo

- Rūpestis -> autentiškumas -> projektavimas į ateitį

Heidegerio terminai savaip:

- Parankiškumas (ready-at-hand), užrankiškumas (present-at-hand), įrankiškumas (in-reach-of-the-hand).

- Pajaustis, tai savirada

- Dasein veiklos (being in) priklauso nuo ribos (rūpesčio) tarp savęs ir pasaulio.

- Užrankiškumui reikalinga gyventi pajungus papildomą sąmonės kanalą (tad nesusivesti), mokytis, įsiminti, ir įprasminti.